|

FALL 2018

*INTRODUCTION

TO UNITED STATES LAW--Lecture

Topic 3: Structure of the Federal Courts

--Last Modified:

Thursday, 09-Aug-2018 08:47:24 EDT

Lecture Topic 3:

Structure of the Federal Courts

Overview

These materials explain the structural

relationships among the U.S. district

courts, courts of appeals, and the

Supreme Court. This lecture also

describes where special federal courts,

such as the U.S. Court of Federal Claims

and U.S. bankruptcy courts, fit into the

structure. Finally, this lecture briefly

describes the work of federal judges and

how they get appointed.

Summary

The judicial power of the United States

is set forth in Article III, section I,

of the U.S. Constitution:

The judicial

Power of the United States, shall be

vested in one supreme Court, and in such

inferior Courts as the Congress may from

time to time ordain and establish. The

Judges, both of the supreme and inferior

Courts, shall hold their Offices during

good Behaviour, and shall, at stated

Times, receive for their Services, a

Compensation, which shall not be

diminished during their Continuance in

Office.

Thus, as you can see from the above

language, the United States Supreme

Court is the only court specifically

provided for by the Constitution itself.

It is the highest court in the United

States and is known as an "Article III

court." Congress has used the power set

forth in Article III to create two types

of "inferior Courts" below the Supreme

Court in a basic hierarchy of authority:

the United States Courts of Appeal--the

basic intermediate appellate courts in

the federal system--and the United States

District Court--the basic trial courts

in the federal system. Because these two

systems of courts are created under the

power conferred by Article III of the

Constitution these two types of courts

also are known as Article III courts.

Only an Article III court may exercise

the full "judicial power" of the United

States (subject to quirky rules in

territories belonging to the United

States). Judges serving on an Article

III court (including Justices of the

Supreme Court) are appointed by the

President of the United States and the

appointment must be approved with the

"advice and consent" of the Senate.

Article III judges are appointed for

life, their compensation may not be

reduced, and they may only be removed by

a process of impeachment for improper

behavior. The lifetime tenure of the

appointment, coupled with protection

against reduction in salary, contribute

to the creation of a judiciary that is

truly independent from the Executive

branch and the Legislative branch of

government. Only Article III courts are

considered "Constitutional Courts."

Article I, Section 8, of the U.S.

Constitution gives Congress the power to

create "tribunals" inferior to the

Supreme Court. A court created under

this power is considered a "Legislative

Court" Congress has used this power to

create two types of judges and courts

which operate as adjuncts to the United

States District Courts: the bankruptcy

judges staff the bankruptcy court in

each judicial district and magistrate

judges staff magistrate courts in the

judicial districts.

The Supreme Court held that Congress

has the power under Article I to create

adjunct tribunals so long as the

"essential attributes of judicial power"

stay in Article III courts. This power

derives from two sources. First, when

Congress creates rights, it can require

those asserting such rights to go

through an Article I tribunal. Second,

Congress can create non-Article III

tribunals to help Article III courts

deal with their workload, but only if

the Article I tribunals are under the

control of the Article III courts. The

bankruptcy courts, as well as the

tribunals of magistrate judges who

decide some issues in the district

courts, fall within this category of

these "adjunct" tribunals. All actions

heard in an Article I tribunal are

subject to de novo review in the

supervising Article III court, which

retains the exclusive power to make and

enforce final judgments.

Additionally, Congress has created

"district" courts in United States

territories under Article 4, Section 3,

Clause 2, of the Constitution which

provides for administration of

territories.

The Congress

shall have Power to dispose of and make

all needful Rules and Regulations

respecting the Territory or other

Property belonging to the United States;

and nothing in this Constitution shall

be so construed as to Prejudice any

Claims of the United States, or of any

particular State.

The district courts in Guam,

the Northern

Mariana Islands and the United

States Virgin Islands are

territorial courts created pursuant to

the power granted under Article 4.

Judges to these courts are appointed by

the President, with the consent of the

Senate, to 10 year terms. Though called

"district courts" because they exercise

the same jurisdiction as an Article III

district court, technically they are

territorial courts. There are 91 Article

III district courts and 3 Article 4

territorial courts exercising Article

III jurisdiction, for a total of 94

district courts in the system. Though

Puerto Rico is not a state of the United

States, the United

States

District Court for the District of

Puerto Rico has been established

as an Article III court.

Congress has created additional Article

III and Article I courts to serve

specific purposes, some of the more

important of which are briefly described

as part of the continuing discussion

below.

How the different federal courts fit

together

Congress has divided the country into

ninety-four federal judicial districts.

In each district there is a U.S.

district court. The U.S. district courts

are the federal trial courts--the places

where federal cases are tried, witnesses

testify, and juries serve. Within each

district is a U.S. bankruptcy court, a

part of the district court that

administers the bankruptcy laws, and

magistrate courts.

Congress uses state

boundaries to help define the districts.

Some districts cover the entire state,

like Idaho. Other districts cover just

part of a state, like the Northern

District of California.

Congress

placed each of the ninety-four districts

in one of twelve regional circuits.

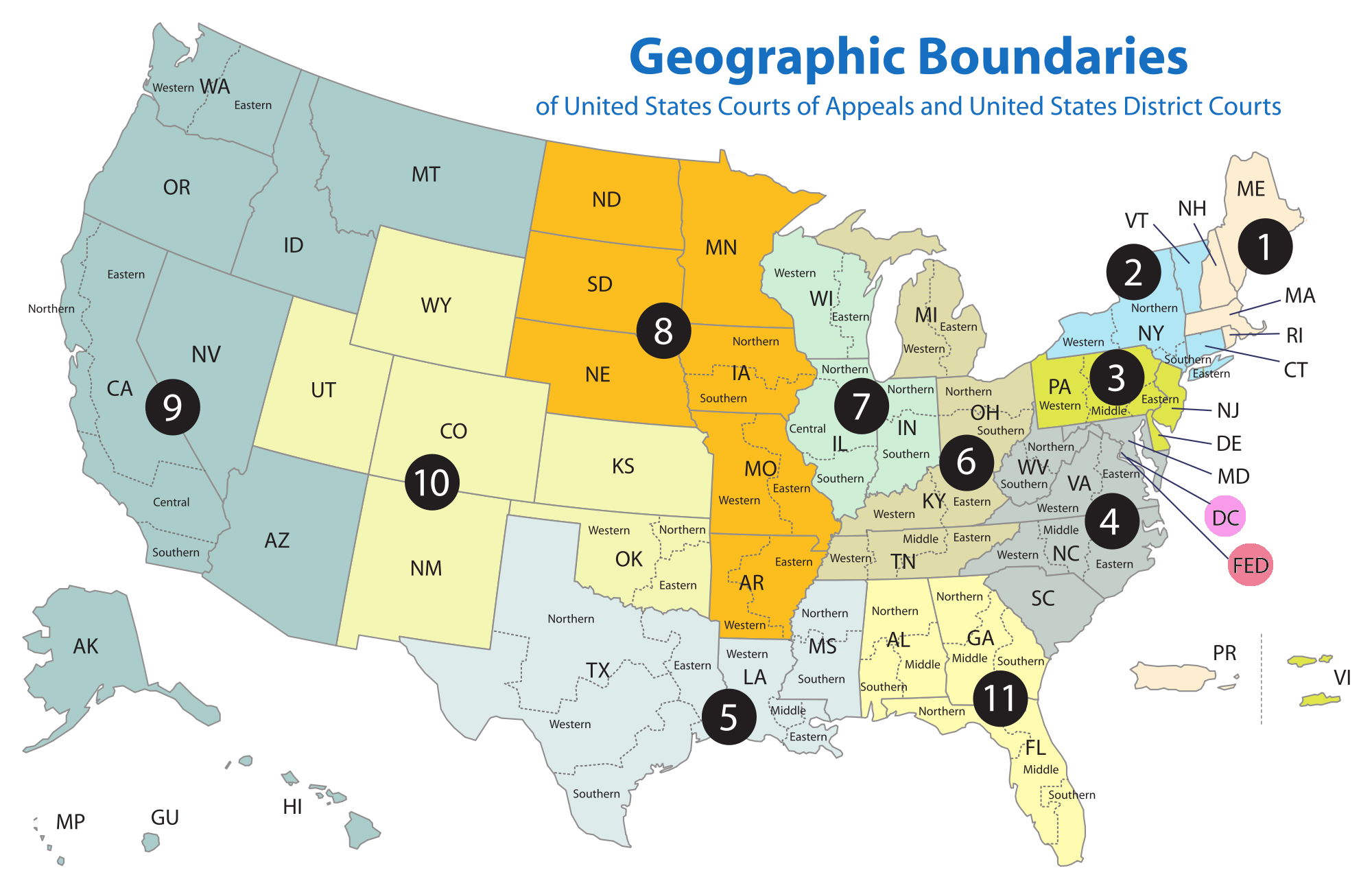

If you look on the map, you will see

only eleven regional circuits identified

by number. For example, Alabama, Georgia

and Florida appear in the region marked

"11" by a black dot. This indicates that

those states are in the 11th

Circuit. Puerto Rico ("PR") is in the

First Circuit. The Virgin Islands ("VI")

is in the Third Circuit. Alaska ("AK")

and Hawaii ("HI") are in the Ninth

Circuit. The twelfth regional circuit is

for the District of Columbia Circuit

which is indicated by the "DC" marking

surrounded by a violet dot. The U.S.

Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia is the circuit court of appeals

for the United States District Court for

the District of Columbia. Each circuit

has a court of appeals. If you lose a

case in a district court, you can ask

the court of appeals to review the case

to see if the district judge applied the

law correctly. For example, Miami is

located in the Southern District of

Florida. An appeal from a case heard in

the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida would be

heard by the United States Court of

Appeals for the 11th Circuit.

An appeal from a decision of the 11th

Circuit Court of Appeals would be made

to the United States Supreme Court

(though there is a procedure by which a

request can be made for a rehearing "en

banc" by a circuit court, about which

more will be said in another lecture).

As emphasized below, the United States

Supreme Court generally is not required

to take up an appeal, in which case the

decision of the circuit court of appeals

will stand.

You should note that the districts in

Alabama, Georgia and Florida were

originally part of the Fifth Circuit.

Effective October 1, 1981, the districts

in these states were split off to form

the Eleventh Circuit. For this reason,

Fifth Circuit decisions from before the

split are considered binding precedent

in the Eleventh Circuit. [Recall that

you were introduced to the concept of

binding precedent in Lecture Topic 2.]

There is also a U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Federal Circuit, whose

jurisdiction is defined by subject

matter rather than by geography. Because

its jurisdiction is not defined by

geography, it is not known as a United

States Circuit Court. This appellate

court is indicated on the map by the

designation "FED" surrounded by a

magenta dot. The U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Federal Circuit hears appeals

from certain courts and agencies, such

as the U.S. Court of International

Trade, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims,

and the U.S. Patent and Trademark

Office, and certain types of cases from

the district courts (mainly lawsuits by

people claiming their patents have been

infringed).

The Supreme Court of the United States,

in Washington, D.C., is the highest

court in the nation. If you lose a case

in the court of appeals (or, sometimes,

in a state supreme court), you can ask

the Supreme Court to hear your appeal.

However, unlike a court of appeals, as a

general matter the Supreme Court doesn't

have to hear an appeal of a decision

that is made to it. In fact, the Supreme

Court hears only a very small percentage

of the cases it is asked to review.

What other federal courts exist?

Unlike the federal trial courts, which

hear only cases arising in their

district or because a litigant is a

resident of the district, two special

trial courts have nationwide

jurisdiction over certain types of

cases: the U.S. Court of International

Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal

Claims. The U.S. Court of International

Trade hears cases involving

international trade and customs issues.

This is an Article III court and judges

of this court have life tenure. The U.S.

Court of Federal Claims hears mostly

claims for money damages in excess of

$10,000 against the United States,

including disputes over federal

contracts, federal takings of private

property for public use, and rights of

military personnel. With the approval of

the Senate, the President appoints U.S.

Court of Federal Claims judges for

fifteen-year terms. This is an Article I

court.

The federal courts in the territories

of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and

the Northern Mariana Islands were

established under Article IV of the

Constitution, as outlined in the summary

section above, though they are called

"district courts" and sometimes are

confused with the Article III district

courts operating within the United

States.

The

United States Tax Court

The United States Tax Court is a

federal trial court of record. It was

created by Congress under Article I of

the U.S. Constitution, section 8 of

which provides (in part) that the

Congress has the power to "constitute

Tribunals inferior to the supreme

Court". The Tax Court resolves disputes

over federal income tax, generally prior

to the time at which formal tax

assessments are made by the Internal

Revenue Service. Taxpayers may choose to

litigate tax matters in a variety of

legal settings other than in the United

States Tax Court. However, other than in

a bankruptcy court, the Tax Court is the

only forum in which taxpayers may

dispute a federal tax assessment without

having first paid the disputed amount in

full. A taxpayer also may bring an

action in any United States District

Court, or in the United States Court of

Federal Claims; however these venues

require that the tax be paid first, and

that the party then file a lawsuit to

recover the contested amount paid (the

"full payment rule" of Flora v. United

States). Tax Court judges are appointed

by the President and approved by the

Senate for a term of 15 years, subject

to presidential removal for

"inefficiency, neglect of duty, or

malfeasance in office...."[4]

The

United States Court of Appeals for

Veteran Claims

The United States Court of Appeals for

Veterans Claims is a federal court of

record that was established under

Article I of the United States

Constitution, and is thus referred to as

an Article I tribunal (court). The court

has exclusive national jurisdiction to

provide independent, federal, judicial

oversight and review of final decisions

of the Board of Veterans' Appeals.

Judges are appointed to the U.S. Court

of Appeals for Veterans Claims by the

President of the United States and

confirmed by the United States Senate,

in the same manner as Article III

Judges.[3] They are appointed to serve

fifteen-year appointments.

The

United

States Court of Appeals for the Armed

Forces

The United States Court of Appeals for

the Armed Forces is an Article I court

that exercises worldwide appellate

jurisdiction over members of the United

States Armed Forces on active duty and

other persons subject to the Uniform

Code of Military Justice. The court is

composed of five civilian judges

appointed for 15-year terms by the

President of the United States with the

advice and consent of the United States

Senate. The court reviews decisions from

the intermediate appellate courts of the

services: the Army Court of Criminal

Appeals, the Navy-Marine Corps Court of

Criminal Appeals, the Coast Guard Court

of Criminal Appeals, and the Air Force

Court of Criminal Appeals.

Federal judges and how they get

appointed

Supreme Court justices and court of

appeals and district judges are

appointed to office by the President of

the United States, with the approval of

the U.S. Senate. Presidents most often

appoint judges who are members, or at

least generally supportive, of their

political party, but that doesn't mean

that judges are given appointments

solely for partisan reasons. The

professional qualifications of

prospective federal judges are closely

evaluated by the Department of Justice,

which consults with others, such as

lawyers who can evaluate the prospect's

abilities. The Senate Judiciary

Committee undertakes a separate

examination of the nominees.

What is an Article III judge?

The U.S. Supreme Court, the federal

courts of appeals and district courts,

and the U.S. Court of International

Trade are established under Article III

of the Constitution. Justices and judges

of these courts, known as Article III

judges, exercise what Article III calls

"the judicial power of the United

States."

Are there judges in the federal

courts other than Article III judges?

Bankruptcy judges and magistrate judges

conduct some of the proceedings held in

federal courts. Bankruptcy judges handle

almost all bankruptcy matters, in

bankruptcy courts that are technically

included in the district courts but

function as separate entities.

Magistrate judges carry out various

responsibilities in the district courts

and often help prepare the district

judges' cases for trial.

Some tasks of the district court are

given to federal magistrate judges. In

criminal matters, magistrate judges may

oversee certain cases, issue search

warrants and arrest warrants, conduct

inital hearings, set bail, decide

certain motions (such as a motion to

suppress evidence), and other similar

actions. In civil cases, magistrates

often handle a variety of issues such as

pre-trial motions and discovery. They

also may preside over criminal

misdemeanor trials and may preside over

civil trials when both parties agree to

have the case heard by a magistrate

judge instead of a district judge.

Unlike district judges, bankruptcy and

magistrate judges do not exercise "the

judicial power of the United States" but

perform duties delegated to them by

district judges. Magistrates are

appointed by the district court in which

they sit by a majority vote of the

judges and serve for a term of eight

years if full-time and four years if

part-time, but they can be reappointed

after completion of their term.

Magistrate judges and bankruptcy judges

are not appointed by the President or

subject to Congress's approval. The

court of appeals in each circuit

appoints bankruptcy judges for

fourteen-year terms.

The judges on the U.S. Court of Federal

Claims are also not Article III judges.

Their court is a special trial court

that hears mostly claims for money

damages in excess of $10,000 against the

United States. With the approval of the

Senate, the President appoints U.S.

Court of Federal Claims judges for

fifteen-year terms. Similarly, judges of

the Tax Court, the Court of Appeals for

Veteran Claims and the Court of Appeals

for the Armed Services are not Article

III judges.

How many federal judges are there?

Congress authorizes a set number of

judge positions, or judgeships, for each

court level. Since 1869, Congress has

authorized 9 positions for the Supreme

Court. It currently authorizes 179 court

of appeals judgeships and 678 district

court judgeships.(In 1950, there were

only 65 court of appeals judgeships and

212 district court judgeships.) There

are currently 352 bankruptcy judgeships

and 551 full-time and part-time

magistrate judgeships. It is rare that

all judgeships are filled at any one

time; judges die or retire, for example,

causing vacancies until judges are

appointed to replace them. In addition

to judges occupying these judgeships,

retired judges often continue to perform

some judicial work.

Judgeships are not allocated equally

among the judicial circuits. For

example, each circuit court has multiple

judges, ranging from six on the First

Circuit to twenty-nine on the Ninth

Circuit.

What are the qualifications for

becoming a federal judge?

Although there are almost no formal

qualifications for federal judges, there

are some strong informal ones. For

example, while magistrate judges and

bankruptcy judges are required by

statute to be lawyers, there is no

statutory requirement that district

judges, circuit judges, or Supreme Court

justices be lawyers. But it would be

unheard-of for a president to nominate

someone who is not a lawyer. Before

their appointment, most judges were

private attorneys, but many were judges

in state courts or other federal courts.

Some were government attorneys and a few

were law professors.

Can a federal judge be fired?

Justices and judges appointed under

Article III of the Constitution (Supreme

Court justices, appellate and district

court judges, and Court of International

Trade judges) serve "during good

behavior." That means they may keep

their jobs unless Congress decides to

remove them through a lengthy process

called impeachment and conviction.

Congress has found it necessary to use

this process only a few times in the

history of our country. From a practical

standpoint, almost all of these judges

hold office for as long as they wish.

Article III also prohibits lowering the

salaries of federal judges "during their

continuance in office." Bankruptcy

judges, in contrast, may be removed from

office by circuit judicial councils, and

magistrate judges may be removed by the

district judges of the magistrate

judge's circuit. Bankruptcy judges and

magistrate judges don't have the same

protections (lifetime appointment and no

reduction in salary) as judges appointed

under Article III of the Constitution.

Why are some federal judges

protected from losing their jobs and

having their pay cut?

Federal judges appointed under Article

III of the Constitution are guaranteed

what amounts to life tenure and

unreduced salary so that they won't be

afraid to make an unpopular decision.

For example, in Gregg v. Georgia, the

Supreme Court said it is constitutional

for the federal and state governments to

impose the death penalty if the statute

is carefully drafted to provide adequate

safeguards, even though many people are

opposed to the death penalty.

The constitutional protection that

gives federal judges the freedom and

independence to make decisions that are

politically and socially unpopular is

one of the basic elements of our

democracy. According to the Declaration

of Independence, one reason the American

colonies wanted to separate from England

was that King George III "made judges

dependent on his will alone, for the

tenure of their offices, and the amount

and payment of their salaries."

For judges who are appointed for

life, what safeguards ensure that they

remain fair and impartial?

Judges must follow the ethical

standards set out in the Code of Conduct

for United States Judges, which contains

guidelines to make sure a judge does not

preside over a case in which he or she

has any reason to favor one side over

the other. For example, a judge must

withdraw or recuse himself or herself

from any case in which a close relative

is a party, or in which he or she has

any financial interest, however remote.

Judges are required to file a financial

disclosure form annually, so that all

their stock holdings, board memberships,

and other financial interests are on

public record. They must be careful not

to do anything that might cause people

to think they would favor one side in a

case over another. For this reason, they

can't give speeches urging voters to

pick one candidate over another for

public office or ask people to

contribute money to civic organizations.

Judges without life tenure are also

subject to the Code of Conduct for

United States Judges.

When do judges retire?

Most federal judges retire from

full-time service at around sixty-five

or seventy years of age and become

senior judges. Senior judges are still

federal judges, eligible to earn their

full salary and to continue hearing

cases if they and their colleagues want

them to do so, but they usually maintain

a reduced caseload. Full-time judges are

known as active judges.

How are cases assigned to judges?

Each court with more than one judge

must determine a procedure for assigning

cases to judges. Most district and

bankruptcy courts use random assignment,

which helps to ensure a fair

distribution of cases and also prevents

"judge shopping," or parties' attempts

to have their cases heard by the judge

who they believe will act most

favorably. Other courts assign cases by

rotation, subject matter, or geographic

division of the court. In courts of

appeals, cases are usually assigned by

random means to three-judge panels.

Review Questions

1. There are ____ judicial districts in

the federal system.

a. 12

b. 13

c. 50

d. 94

e. 100

2. Congress uses ____________boundaries

to help define federal judicial

districts.

a. municipal

b. regional

c. state

d. geographic

e. federal

3. Only __________can be removed from

office by circuit judicial councils.

a. Supreme Court justices

b. appellate judges

c. district judges

d. bankruptcy judges

e. Court of International Trade judges

4. True or false? Several federal

judicial districts include more than one

state.

Your answer: ___ True: ___ False.

5. True or false? The Supreme Court of

the United States will usually decide

whether a state supreme court or federal

court of appeals made a correct

decision, if a party to the case asks it

to.

Your answer: ___ True: ___ False.

6. Supreme Court justices and court of

appeals and district judges are

appointed to office by the President of

the United States with the approval of

the ______________.

a. U.S. House of Representatives

b. U.S. Senate

c. U.S. House of Representatives and

the U.S. Senate

d. Judicial Conference of the United

States

e. U.S. Department of Justice

7. True or false? The number of

justices on the Supreme Court is 9.

Your answer: ___ True: ___ False.

8. Supreme Court justices and court of

appeals and district judges can be

removed from the bench if they are

a. found by Congress to have made too

many incorrect decisions

b. found by Congress to be incompetent

c. impeached and convicted by Congress

d. impeached and convicted by the

President

e. any of the above

9. Under the _________, a judge must

withdraw from any case in which a close

relative is a party.

a. Constitution, Article III

b. Code of Conduct for United States

Judges

c. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

d. Fifth Amendment

e. Monograph 111

10. True or false? A federal judge who

believes the law should be changed in a

certain area can petition the chief

judge for a case that will allow him or

her to issue a decision that modifies

the existing law.

Your answer: ___ True: ___ False.

|